#38 Wordsmithing with Barry Yeoman

“That was the first time I felt like I had power as someone who stutters”

BIO

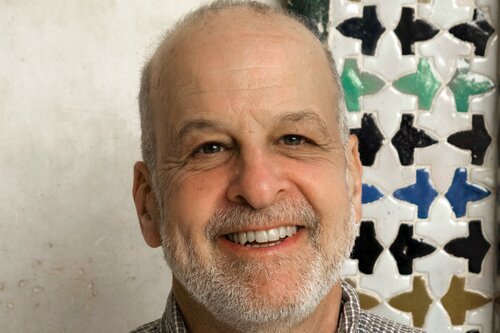

Barry Yeoman is an award-winning freelance journalist in Durham, North Carolina. He works in both print and audio, putting human faces on complex social and political issues. He also teaches journalism at Wake Forest University and Duke University. He has been involved in the stuttering self-help movement since 1992, and most recently wrote about stuttering and neurodiversity for The Baffler, and about Joe Biden’s stutter for The Nation.

Listen to this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts or your favorite podcast platform. You can also watch the interview on YouTube.

EPISODE HIGHLIGHTS

0:00 - 3:42 Intro

3:42 - 16:11 Stutter Talk Podcast

16:11 - 32:16 The National Stuttering Project

32:16 - 58:50 How Do We Create an Open Space Event

58:50 - 1:18:38 The Top Five Qualities of a Journalist

RESOURCE LIST

MORE QUOTES

“I was just listening. And so stuttering makes me a better listener.” - Barry Yeoman

“Stuttering makes me less intimidating. I show up at somebody's door and they're already nervous about talking to the journalist. Then I show up and I'm five feet and three quarters. My shirt's wrinkled and I stutter. And so I become less intimidating. And so people open up more and relate to me.” - Barry Yeoman

TRANSCRIPTION:

Uri Schneider: Good morning, it is a beautiful day. Uh, for some people on the east coast snowed in for all of us, you know, getting through the, the days that will be remembered for, for many, many stories to come about 2020, but it's, uh, it's a season of giving. It's a season of reflecting. It's a season of, of connecting and communicating around what we care about most.

Uri Schneider: So it's a big privilege. My name's UR Schneider. I lead Schneider speech and I really, really have goosebumps the, the pleasure to host this conversation with Barry Yoman. Uh, so thank you, Barry, for taking the time I'll spare the long intro, but Barry is a person who, as a professional journalist freelancer teacher in both wake, wake forest, as well as duke, um, An extraordinary human being and his journey with stuttering and knowing it from the inside.

Uri Schneider: Uh, we had a wonderful conversation two days ago. We thought we'd get on for a few minutes. As often as the custom ended up being much longer. Uh, there's so much to learn so much to share. And I'm so grateful that in your schedule took the time to have this conversation. Barry,

Barry Yeoman: thank you. Uh, really happy that I'm here URI and thank you so much for having me

Uri Schneider: wonderful.

Uri Schneider: So as we said, it's, it's an unscripted thing. What would you feel? You know, you'd like people to know about you that feel significant in

Barry Yeoman: sharing. Wow. Well, you know, it's, it's hard to separate out, uh, my story, your story, everyone's story from the fact that it's 2020. Right. And I think that for many of us, certainly for me, um, this has been a year of.

Barry Yeoman: Figuring out what matters what's, what's important. And it feels like that has come at a moment where I've been, I've been thinking about stuttering in new ways. Um, uh, with, with a big boost, from a lot of people around me who are thinking original thoughts that I'm, um, stealing and, and trying to integrate in, into my own, uh, under, under, under, under understanding about my stutter.

Barry Yeoman: And maybe we start with the end and we work backward, which is that after, after a lot of years of, um, first thinking of my stutter as a curse, and then. Thinking of my stutter as a benign thing that I live with. And then thinking about my stutter as, um, a benign thing that I live with proudly, I'm coming to think of my stuttering as a blessing, and that is it's head spinning.

Barry Yeoman: And it's really a realization that I've only fully come to in the last, I don't know, couple of years.

Uri Schneider: So we had that conversation on the phone just about that idea of the lifespan perspective. And I know we both, uh, love and enjoy and, and certainly you have participated many times. I have had the privilege as well. My father, wonderful stutter talk podcast. If anyone has not discovered that yet, uh, whether you're a professional, whether you're a person who stutters or someone who cares about stuttering, It is a premier, you know, resource of conversations, over 700 conversations with people who stutter from around the world, researchers, professionals, thought leaders and new new faces in the crowd.

Uri Schneider: Um, so the thought about you, Barry, you know, as someone that people turn to almost as an elder statesman in the stuttering community, and when you shared what you just shared, uh, I just wanted to highlight that idea of that evolution. And I think a lot of people five years ago, 10 years ago, could have looked at Barry Yoman as he's arrived, he's at the destination.

Uri Schneider: Could you share a little more about, about that evolution that you were describing and kind of like the stages of life and what it makes you think going back, as you said, if I knew then what I know now, the kinds of messages that may have been helpful and at the same time may have been incomprehensible at an earlier stage.

Barry Yeoman: Yeah. Um, and if I, and, and, and, and I look at myself 10 years ago when I had definitely not arrived and, and I don't think I've arrived yet. I think I'm just at another point in the journey. Right. Um, so I, I, I grew up, um, in a high achieving community, uh, in New York state, um, where a good portion of my high school class was Ivy league bound.

Barry Yeoman: And there were certain expectations of achievement put on us by, by our peers, by our teachers, by our families. Um, that that was about accomplishment was about transcendence of the last generations. Um, and was. About metrics. Um, everybody not only knew their own S a T scores, but knew everybody else's S a T scores.

Barry Yeoman: And so what was measurable was what was important. Um, I could tell you how fast I could run the quarter mile. I could tell you how many pull-ups I could do. Um, uh, I could tell you what my differential aptitude scores were in eighth grade, and, um, that they told me that I should be a journalist and if not a journalist, a playground attendant.

Barry Yeoman: Um, and so there was this huge honking metric, which is how many words I could get outta my mouth in a minute. And by that metric, I failed, I stuttered. More more severely than I do now. Uh, a lot more. Um, I found recently a cassette tape of an interview. I did, uh, when I was 20 and it was, it was a hot mess, um, a lot, lot to struggle, lots of self consciousness.

Barry Yeoman: Um, and, and so that was the standard of my, my community of myself and of the speech therapist. I went to, uh, how fluent were you? And that, that continued all the way through my last day of speech therapy into my twenties. Um, like a lot of new Yorkers in my generation, I went to see Dr. Martin Schwartz, whose book stuttering solved claimed that if you altered the way you, your, your air, your airflow happen, that happened that you had a 94% chance of succeeding at fluency and I didn't succeed.

Barry Yeoman: Um, and so finally at 27, I said, screw this and I quit speech therapy. And I've got, I've got a copy of my records from that speech therapy, which, which talk about what a frustrated, resistant, hostile patient I was. Um, I was fluent in the therapy room and. I was putting a lot of pressure on myself, outside the therapy room to match that.

Barry Yeoman: And when I didn't match that, it snowballed, uh, it, it, um, it added to my stress and I studied more and felt more frustrated.

Uri Schneider: Can I interject or would it take you off course? No, please, please do. There's a question that I always ask someone when I meet them. And, and some it's more often the case that I meet people who've already been through some sort of experience with speech therapy.

Uri Schneider: Um, and I have two questions I'd like to ask. And one is what was the least helpful, most unpleasant part. And then what was one thing that you learned along the way, whether it was from that therapist or on your own, or from a peer or a parent or some caring adult who knows? Um, so in, in, in, in the totality of the experience, what would you say was.

Uri Schneider: Was maybe one positive nugget that you picked up along the way, even if it was to realize something in yourself. Mm-hmm uh, and, and what was maybe the most outstanding frustration? Cause I think's helpful to, oh yeah.

Barry Yeoman: Well, I'll start with, with, with, with a positive nugget because it, it was, it was enormous, which was that my first speech therapist told me how

Barry Yeoman: to, to deal with bullies and it was brilliant. Uh, there was a kid who mocked my stutter every day. Uh, it made me frustrated and angry and sad and lonely. And my speech therapist said, why don't you pretend he's auditioning to be you in a movie and tell him how good his performance is. Which, which seemed crazy.

Barry Yeoman: Right. But I was desperate. And so I did, I did exactly that to no effect the first day. And then he came back the next day and he mocked me and I said the same thing. And he stopped and said really. And the third day he came and wanted to, to be my friend. And that was RI the first time I felt like I had power as someone who stuttered.

Barry Yeoman: I was, were you at that time? I was like 10, maybe. Um, wow. But it felt, it felt fierce. And, um, That was, that was like that, that, that was the high moment of almost 20 years of therapy. Wow. Um, I think that like all the techniques I taught were kind of equally effective or ineffective. Um, and, and I acquired a bag of tools that I still use, um, in kind of a light way to get me through hard days.

Barry Yeoman: I know how to make sure that my air doesn't stop flowing. I know how to, um, how to cancel and repeat words and, and how to slow down and all that stuff. Um, but I think that the hardest part, the least useful. Was when I was actually measured when, when a therapist decided that my measure of success was to bring me out into the wild and take a stopwatch to me.

Uri Schneider: And it's so interesting that that was what you led with in terms of the culture that you were surrounded by growing up was, was about measuring, measuring up. Yeah, certainly in my high school years, I was, and, and many of my years grew up with, let's just say most of my colleague friends are not speech therapists.

Uri Schneider: Um, but there was a, you know, that just wasn't, you know, it was doctors and lawyers and brokers and investment banking. Um, but the idea that being measured, I think for anybody, right. Is a feeling of being judged yeah. By someone else for your worth. And your performance is up to speed or it's not up to snuff, but then if you're living in a world or in a home.

Uri Schneider: Anyone, I'm not speaking about any individual, but any, anyone is living with that. They're all the more sensitive to it and trying to find their worth and their, their place and their way.

Barry Yeoman: Yeah. And I should be clear. I bought into measuring culture completely. I, I, I, are you still in, less, so less, so yeah,

Uri Schneider: a much less, how did that evolve talk about when did that switch happen?

Uri Schneider: What,

Barry Yeoman: what you, oh God, you know, probably about the time that I quit speech therapy was about the exact same time that my friends started to die of aids and nothing recalibrates you faster than, uh, losing people you love. Um, I quit speech therapy at 27. My first friend died of aids when I was 28. And, uh, so it, so those two, I, I it's, it's interesting that you asked that because I never made that connection in terms of time until right now, but it was within a year.

Barry Yeoman: And so there was this period, there was, there was a five year period between my quitting speech therapy and my finding the uttering self-help movement. And those five years were the apex years for losing friends. And so I went through this huge recalibration, um, period. Now I was already on that path because.

Barry Yeoman: Uh, like, like you became a speech therapist, I became a journalist, you know, we, we were both downwardly, downwardly, mobile in relationship to our, to our C communities of, of birth. But

Uri Schneider: I'm honored. I'm honored to have any, any kind of association or, or similarity

Barry Yeoman: with you. Thank you. Um, so I was already starting on that journey.

Barry Yeoman: I, I was, I was taking low paying jobs that were satisfying. So, you know, basically as soon as I was outta college, I stopped thinking about the metrics, but I really stopped when, um, these friendships I had developed in my adult life came crashing to a halt as people died. Um, and so I was really primed when I discovered.

Barry Yeoman: The stuttering self-help movement in the form of what was then called the national stuttering project, the precursor to the current national stuttering association. And the very first gathering I went to was an international conference in San Francisco. So it's 1992, I'm 32 years old. I walk into this room with hundreds of people from around the world.

Barry Yeoman: And not only is it the first time I've been in a room with more than one other person who stuttered, but they were so cool. They were funny and they were good looking and they were accomplished and they were warm. And, um, and.

Barry Yeoman: Many of them seemed a lot less hung up about their stutter than I was. And I could, I can tell you the night, it all changed. It was during, it was during that conference. Um, uh, I've thought about this recently when I, um, when I spoke to friends, uh, the, the, the association of young people who stutter, uh, and, you know, there was all this great stuff that happened at the conference, but one night, eight of us ditched the conference.

Barry Yeoman: This was in San Francisco, um, ago, um, eight of us left and we went to, to the, the, the, uh, the mission district, which, um, was, and is a largely, uh, uh, Latino neighborhood in San Francisco. We went to eat Salvadorian food and there were eight of us, four Germans and two poles and one other American in me. I like the beginning of a joke.

Barry Yeoman: I know. I know. Well, well, just to pile on and a server who didn't speak English, um, who was so freaked out by our stutters that she made us prepay our meal. Um, but we didn't care because we, we kept ordering CCUs and, um, I wanna say sangria and we were eating and drinking and one of the polls didn't really speak English.

Barry Yeoman: So the other poll translated for him and. We were talking about things like what it was like to be in Germany when the wall fell. And we weren't talking about stuttering though. Lord knows we were stuttering and, and it felt so normal and so alive. And no one was hovering over with a stopwatch or telling us we had overstay our 45 minutes or, um, or anything.

Barry Yeoman: It was pure light. It was pure warmth. Uh,

Uri Schneider: you described that as the night, it all changed. And, and it consisted of a group of international people who stutter. Yeah. Who didn't have. Uh, preexisting friendship, right. Uh, but, but connected at a conference, ditched the conference, anyone that knows conferences knows the real magic happens between the sessions or when you step outside.

Uri Schneider: Yeah. Not to say the sessions are not amazing, but, uh, and when you describe it, you talk about just having conversations about current events and things in the world and things he cared about it. Wasn't talking about the in inner workings of stuttering and figuring it out. And how do you manage and how do you cope and why do you think you stutter, but connecting with these people and the carefree, warmth, and the flow and the feeling that there wasn't a stopwatch hovering.

Uri Schneider: I'm wondering in contrast to what, in other words, besides measured by PE you know, speech therapist at times, this experience was you're describing it as the night, everything changed and in some ways it sounds so LAE fair. It sounds so, so casual. So. Matter of fact, every day daily life for so many people, but I wonder what was different about it that felt so significant

Barry Yeoman: when you grow up with your primary communal goal being achievement, um, you don't particularly plays value on, on the times you can figuratively or literally lie on your back and stare at the ceiling.

Barry Yeoman: You, you, you don't necessarily value human connection. As as primary,

Barry Yeoman: I always had really close friends. I always understood the value of friendship, but. The, but the voice was always pushing me toward achievement. Even, even though I had gotten off the, the track that where I was supposed to be, you know, a doctor, a lawyer or a stock broker. Um, and so

Barry Yeoman: it, it would be many years still before I would realize that the accumulation of people who stutter in my life, um, many of whom are my closest, closest friends

Barry Yeoman: were

Barry Yeoman: the biggest part of my life, treasure or my all, all my friends, uh, Are the biggest part of my life, treasure and people who stutter are a large subset of that, that if the people who stutter, who are in my inner inner circle, um, were not there, I would be impoverished. And if I didn't stutter, they would not be there because I would never have met them.

Barry Yeoman: Um, that started with that night, uh, the, the, the, the seed was planted that night. I didn't know what the, what the tree would look like. Um, honey fruits. Yeah. Yeah. You, you, you, no, there are. , there are two people from that initial weekend that remain, uh, two of my closest friends and that's going on 30 years now.

Barry Yeoman: Wow.

Uri Schneider: I can't help, but, uh, have shivers, you know? Um, and I know many people you asked not to be distracted by which of your friends are here, but many people are enjoying the words you're sharing. And if you feel these are words worth sharing, uh, for no purpose, other than the fact that I think part of why Barry carved the time was that I think this conversation could.

Uri Schneider: Enrich the lives of other people who are on that journey. And in some ways may resonate with something here or it may spark a question or a thought and, uh, it may take them to another conversation. So if you feel inclined to share or to comment, I will try to monitor those comments and certainly appreciate the sharing of this conversation and, and Barry's wisdom and the treasure that is this, this moment right here.

Uri Schneider: So thank you to everybody that's

Barry Yeoman: here. Uh, thank you. Thank you for that, for that, for, for, for those words too, a hundred

Uri Schneider: percent. Um, I, I, I truly, it's not, I, I try not to share more than I should, but I get, I get private comments from people is the most touching thing about these conversations and what's made it worth the effort to keep it up.

Uri Schneider: Is people who are students of speech pathology, people who are people who stutter, who are wondering about becoming professionals in this field, as researchers, as clinicians and people who stutter around the world far and wide. They talk about the feeling of access to people like you, Barry people like Michael Sugarman, people like Jerry McGuire, people like Vivian Siskin, then everyone in between, um, each and every person, whether it's a person who's a better known name or a lesser known name, each person has a story.

Uri Schneider: And the purpose of whatever we're doing here is really just sharing these stories. Um, and uh, giving people access. I I'm, I'm obsessed with that. The idea that, you know, the world has always been a place where people have access. There are the haves that have nots, whether it's geographic, whether it's, uh, monetary, and if we can create bridges, the, uh, that's my little soapbox there, but, um, there are many people that are enjoying and, and please continue to enjoy and to share.

Uri Schneider: So Barry, I couldn't help, but notice it it's striking how the experience you had is within the context of, of a trajectory of your life. and so like finding your independence and getting out of that, what you said, being bought into bought into the metric system and, and measuring things and measuring by achievement.

Uri Schneider: So that shift was happening. Do you think that night could have happened? Do you think you could have gone to that conference at the age of 15? Oh, at the age of 20? Could you share on that? Cause I think, I think it's, it's so powerful. We all know that people that go to conferences sometimes have such watershed experiences, many people that have good experiences.

Uri Schneider: It is a watershed moment. And at the same time, there's, there's this hope that we could get everyone to have that moment, if we could just get them to come into that room. Right. And some people are resistant. And I was wondering if you could share on that, being someone who had such an experience, but also the perspective of what your readiness

Barry Yeoman: was.

Barry Yeoman: Oh, I think I would've been completely resistant earlier. Um, uh,

Barry Yeoman: But that said, if you had dragged me into the room and I I've always been somebody who worries to make connections. Um, I, I remember I was 15 and my family went to Disney world. And, um, when we were coming home, um, the airport in New York was snowed in. And so they, they canceled our flight and, and, um, put, put us up at, at an airport hotel.

Barry Yeoman: And like, I be lined two of the nearest, uh, uh, 15 year old male I could see and just had a conversation. Um, And looked him up later, you know? Um, and so, so I think if you had gotten me in the room, I would have, I would've been Belin to somebody who felt safe. Uh, and while I might have been resistant to the message that it's okay to stutter, it may even be cool to stutter.

Barry Yeoman: Um, I would've been open to the, the human contact. And so

Barry Yeoman: that's my hope. I mean, we, we have all of these eight year olds, 10 year olds, 18 year olds who are coming in to friends now who, um, who. I don't know if they're coming voluntarily. Um, at first, uh, if they're thinking that this is gonna be something that fixes their stutter, but you see what happens when, when young people show up at any self-help organization conference, um, when, when kids go to say, um, start acting, uh, on a stage, uh, the hope is that whatever expectations you had going in or whatever reticence you had going in, you shed.

Barry Yeoman: And I think I would've had a lot of reticence going in earlier in my life. And. Regardless of whether I had, she, I would've shed the, have to fix my stutter attitude. I would've been open to the relationships

Uri Schneider: picking up on that. One of the other questions I often ask that eight year old that may be brought into our office.

Uri Schneider: My father always says they usually are not the ones that picked up the phone and, uh, scheduled the appointment, you know? Right. So I say, you know, whether they're eight or 18, um, did you come here because you wanted to, or your parents kind of schlep you in and, and if it's the form or the ladder I'm interested in, what, what drew you here?

Uri Schneider: What was the attraction or what was the hope? And then what was the resistance or were the things you might have been concerned of? What are some things, you know, you and I talked about the idea that, um, creating space and permission for different people to have, um, Different experiences and different feelings and, and resistance.

Uri Schneider: I was wondering if you could just share on that. In other words, the younger barrier, as you said, you might have gotten there and made some really meaningful connections, even if you might have verbally resisted going originally. But then of course there may have been something that you might have been encouraged to do or pushed to do that might've pushed a button that would've actually soured it for you.

Uri Schneider: Yeah. And, and while the overwhelming majority of young people who participate and I can't emphasize, or amplify enough the value and importance of young people, especially, but all people feeling a part of something bigger than themselves, not feeling like you're alone, no matter what you're living with.

Uri Schneider: So self-help community is so, so incredibly. And at the same time as with anything powerful in life, it doesn't come without people that have a different experience or an aversive reaction. Uh, it doesn't mean that the community is not a good community, but creating that space so fewer people's buttons get pushed, but the space is there to have a positive experience, whatever you're ready for.

Uri Schneider: You have any insight on that, the younger Barry or young kids that you see and you're so involved, what are your thoughts about that in terms of how do we create an open space even within self help, where people that are still resistant can be in the tent, even with that resistance.

Barry Yeoman: That's a great question.

Barry Yeoman: And I would expand that to say young adults and older adults. It it's absolutely not just it's. Um, we've been talking about that a lot among ourselves, uh, in my little posse of stuttering friends, um, because, um,

Barry Yeoman: When you find yourself having reached an epiphany

Barry Yeoman: you're you tend to become militant about it? Um, no, no more militant non-smoker than an ex-smoker. Right. Um, and so there are moments when I just wanna burn down the house. I, I, I like like every, every bad attitude about stuttering that I define as bad. I, I wanna, I want to, I wanna get rid of it. I, I, um, I don't have the patience for, um, For, for people who want clinical drug trials, you know, or, you know, what, what, what, what, whatever it is.

Barry Yeoman: I, um, I, at my most, um, in transient moments, I wanna, you know, say my way is the right way and, and, you know, you know, y'all come here. Um, and then I come to my senses and I remember that I am somebody for whom inclusion, diversity, um, has teeth. It matters. It's something I actively work toward and that I can't be inconsistent here.

Barry Yeoman: That, um, that in fact, we want to create the biggest possible tent. And,

Barry Yeoman: you know, I, I think about, I think about something I, I heard Chris Constantino say recently, and I'm gonna try to paraphrase and maybe butcher, but basically it was to the effect of that. We are, if we are asking for the freedom to stop chasing fluency, see, then we should be granting freedom to those who still wanna chase fluency, that, that we need to be consistent in our guiding principle, which is that there is no one path.

Barry Yeoman: there's no, there's no right way that everybody has to follow that. I might, um, say that we, we, we live in enable us society that has to accommodate us. It has to change. Um, we have to, um, we have to work on the evil of ableism that privileges, uh, fluent speech, all of which is true, I believe. Um, but that doesn't really help you if you're looking for a job at a restaurant and, and regardless of what the law is or what you believe should be the case, um, you might get hired with a stutter, but you won't get hired with a severe stutter.

Barry Yeoman: And for those whose reality is that job market, who am I to say, um, stutter as much as you want, you know, you know, screw the bosses, you know, that's, that's, that's a very privileged thing for me as a college educated white guy to say, uh, this

Uri Schneider: is such an important point, Barry. I want you to continue to go with it where you wish.

Uri Schneider: I think it also speaks to our newly elected president and the expectations of him. Yeah. Uh, and his identity as a, as a person who stutters and how that is shared versus how much that is not put front and center and how overtly he should stutter versus how. Acceptable it is that maybe he switches words and maybe he stuffs it in sometimes, clearly he's a person who stutters and still contends with his stutter and the judgment and conversation around how he manages it.

Uri Schneider: Expectations. I think what you're talking about is right on that.

Barry Yeoman: Yeah. Um, as you know, I've written about, uh, pre president, like whiten and, and I, um, was at that first national stuttering association, um, conference where he spoke in 2004 and I challenged him during, during, during the, the Q and a, because what he, he seemed to be saying at the time.

Barry Yeoman: And I think he's evolved since then. Is that, that, that you can do anything you want, as long as you apply yourself to, oh, getting rid of your stutter. Like I did. and I asked him during the Q and a, are you saying that for a kid to succeed, they must stop stuttering. Um, or are you saying that, um, a kid can COE can succeed as an adult and stutter?

Barry Yeoman: And at the time he, he hedged, he, he said, well, well, of course anyone can, can succeed, you know? No, you know, no matter why, but he said your, your ability to convey a message is gonna be limited by the listener's willingness to receive the message. Now what I know. Is that Biden has evolved a little bit, but what I know even more is that Biden's message has been received in really helpful ways, by a lot of people.

Barry Yeoman: And you just have to, to look at, at Braden Harrington who spoke at the democratic national convention, who took that message, took inspiration from it and then made it his own, which was not the same as Joe Biden's message. Braden Harrington got up in front of the camera and in front of how many tens of millions of people stuttered openly something that his role model doesn't do.

Barry Yeoman: So even though the. President Biden, um, gives one message. That doesn't mean that that message does, does, does, does doesn't evolve through the generations? Um, Joe Biden is in his late seventies. He came of age at a certain moment in the conversation about stuttering. He is not likely to evolve too much beyond where he is now.

Barry Yeoman: Um, because that's, what's, you know, that, you know, that that's what made him president. He, that he, he, um, he accomplished in spite of his stutter. Um, but you see the seed get transferred from. Biden to Braden and you see maybe the rootstocks the same, but the, the fruit looks different. And then what will Braden Harrington transmit took to the next generation?

Barry Yeoman: Um, and just that, just that transmission makes me want to be more inclusive. Um, let's, let's, let's, let's not even talk about the people who come in at point a and we wanna bring them to point Z, but maybe we bring them to point C that's that's something too. Um, maybe somebody never wants to stop working on fluency, shaping, but they love themselves a little more and they.

Barry Yeoman: Feel like they have a better community structure and maybe they, they, they don't beat themselves up quite so much. That's,

Uri Schneider: that's not sometimes that's so, so important. And it goes back to the measure, right? And, and whether the achievement is the measure or whether it's being on the path and being in the dance and being on the journey and being engaged, I think I just wanted to riff off that and then take it where you want.

Uri Schneider: I think there's also the idea of Joe Biden versus the president elect Biden. There's the individual man. And then there's the man who is a politician. And by VI being a politician, you represent others and you represent the office, whether you're holding one office or another. And I think it's very striking the time he chose to take out of his schedule with more than 10 young people.

Uri Schneider: I know who stutter that during the campaign, he would take more than 20 minutes to talk to Braden on the phone. More than that with others. That was the man that was Joe Biden. That was Joe Biden, who grew up with a stutter. And I think we don't hear that story or see that story as much, cuz I think when we see him and hear him now in the position he's in, there's also that identity or that performance of the role, he, the shoes he fill in that sense.

Uri Schneider: And I think it's striking that he chose to have bride Braden, I think as his proxy yes, of maybe the personal Joe Biden, the real Joe Biden as an individual, that was a choice that didn't have to be made. It was a bold choice. And maybe, maybe I'm wondering if it was a message and a model and having met John Hendrickson, of course, you know, maybe these were things that he chose in, in a subtle, indirect way to portray and bring out.

Uri Schneider: Maybe we need to give him more credit that way

Barry Yeoman: maybe. or maybe just like my childhood speech therapist told me that you, you diffuse a bully. He was diffusing a bully. He, um, he,

Barry Yeoman: he might have known that the next three months there would be all these people on the other side, making fun of his stutter and that the easiest way to diffuse it is to address it directly. Uh, and, and so, um, he finds a really sympathetic way of, of addressing it directly. And I'm not, I'm not. Um, in any way saying that's a bad thing.

Barry Yeoman: I think, I think that in some ways me telling the schoolyard bully who will not be named that he did a really good job of, of auditioning to play me in a movie. And suddenly the power of the bullying was diffused, maybe Biden and his team decide, oh, you know, they're, they're gonna, they're gonna mock my stutter.

Barry Yeoman: You know, let them try to mock Braden Harrington stutter. And, and so, so I wonder if he was in some ways doing the same thing that I did when I was 10.

Uri Schneider: I'm gonna leave room for that. , but I, I do wanna put forth that other possibility. And it's based on my conversations with Braden and his family. And I think the interview with John Hendrickson mm-hmm and the, as you said, the speeches that, that Biden gave at times when he was not a nominee.

Uri Schneider: So right after he lost the democratic nomination process, uh, to Barack Obama, he was sort of not here, not there, you know, didn't have a campaign in action and he spoke at the American Institute for stuttering, right. And those videos where he tells his story are more open, more emotional, more, more gripping in my opinion than any other.

Uri Schneider: And I think it's partially because he had the latitude. And so I think if one looked at the different statements that are made over his. You know, trajectory of his career in different spaces, different audiences. I'd like to think that Braden Harrington wasn't, uh, you know, a puppet of, of, uh, of a purpose or a function to deflect, uh, the bully behavior.

Uri Schneider: Uh, there could be that function as well. But I think in Braden, the same feeling that so many people saw, whether they stutter or not the courage, the bravery, the openness, I think that's, I choose to think, uh, without, you know, making a case, but I think the Joe Biden in his heart of hearts was equally enamored by Braden for being a young person who did things that many of us much older than him still couldn't do to get up and speak and say what we have to say, no matter how it comes out.

Uri Schneider: And I just am in awe of that kiddo.

Barry Yeoman: Well, he is awesome. He is awesome. And it is very clear also that, um, that, that Joe Biden's affection for him is genuine. Uh, what's what is, what is an interesting and open question for me is when VI, when, when president elect Biden becomes president Biden, um, and likely one term president Biden, he's, he'll be in his eighties in four years, uh, and may not, may not run for reelection who knows.

Barry Yeoman: Um, does that give him more latitude then to be more open, be more of an advocate? Um, we already see not just his political adversaries, but even journalists, um, um, taking potshot when, um, when he, uh, Botched, but then corrected the last name of the, his nominee for HHS secretary and some, some prominent journalists immediately tweeted out the,

Barry Yeoman: the mistake as if he had just given away the nuclear code. Um,

Barry Yeoman: at some point he may do aside that he's, he's done, he's done stuffing any of it under his hat that, that he's not running again, that he's the president of the United States. And, um, and um, that he's gonna be, um, he's gonna be forthright in talking about his stutter. And, and,

Barry Yeoman: you know, be more open about it than, than he, than he he ever has before

Uri Schneider: I think. And you just put on display. I, I was well aware going into this, that I'm speaking with a journalist of the highest order. So I'm outta my league and defer to you. And, and a lot of what you just reflected is so profound and gives me a lot.

Uri Schneider: I'll be listening to this again. I hope others will too. Can you talk about how a, a kid who stutters ends up in a, in an industry, a profession, a career of teaching of journalism, which is all about words and in some ways is, uh, so fitting and in other ways, so surprising. Yeah.

Barry Yeoman: So. I like to say that I feel like I popped out of the womb, a journalist.

Barry Yeoman: I was, you know, I was publishing a neighborhood newspaper handwritten with pencil at 11. Um, and I grew up in a community where being a journalist was not considered upward mobility and certainly got messages that, that didn't make a lot of sense. Um, if you stuttered and, and I, I, I, I, I was, I was, I was editor of my high school paper.

Barry Yeoman: I was a good editor of my high school paper, um, um, you know, ticked off our principal more than once. And. Also

Uri Schneider: seems like we have a lot more in common than we have found before. I spent more time outside the principal's office than I did in class. Yeah.

Barry Yeoman: I, I actually had the principal report me to the police when I would not divulge the name of a campus drug dealer who I'd written about in the school paper.

Uri Schneider: Um, so, so you didn't just give your speech therapist a hard time. You were an equal opportunity.

Barry Yeoman: Oh yeah, yeah, yeah. I, if not. Well, and it was this weird combination of, um, being a good kid and being, having an anti-authoritarian streak. Yeah, yeah. Right there with you. Um, so, um, what's that, what's that verse from first per first Corinthians, you know, um, as a child, I did childish things and then I put away the childish things I thought, okay.

Barry Yeoman: I'm entering college, I'm entering adulthood. I'll do the adult thing. And I entered as a psych major, which lasted for three days. And then I went to a journalism department orientation at NYU and I said, that's what I am. You know? And so again, I, I did this in my head thinking it was in spite of my stutter that, that I've got this huge obstacle.

Barry Yeoman: I can't talk. Right. But I really wanna do this. So I'm gonna, I'm gonna, you know, you know, be the track star with one leg, you know? Um, and it took a long time, like, Into my thirties before I started to realize that my journalism I'm sorry, that my stutter actually made me a better journalist. And it was a process.

Barry Yeoman: It was anion of realizations. Um, that first I didn't particularly like my own voice, so I just knew how to shut up and listen. And you know, early in my career, I, I, I, I worked for weekly newspaper in North Carolina here, and I cover the state legislature and I would be sitting in the press room. And there were all these swaggering journalists who were telling stories and N never listening as far as I could tell, but I wasn't doing that.

Barry Yeoman: I was just listening. And so stuttering makes me a better listener. And then I realized that stuttering makes me less intimidating. And so I show up at somebody's door and they're already nervous about talking to the journalist, uh, and increasingly, you know, the accomplished journalist. And then I show up and I'm five, six, no, I'm not.

Barry Yeoman: I'm five, five and three quarters. Um, My, my shirt's wrinkled and I stutter. And so I become less intimidating. And so people open up more and

Uri Schneider: people relate to me. I'm already disadvantaged. I'm already disadvantaged. I'm six feet tall. Yeah, I don't stutter. Yeah. And, and I can't, and I can't stop the fact that it happens to be that the shirt is iron free, so it doesn't have wrinkles.

Barry Yeoman: Oh my, I, I even, even, even iron am free shirts of mine wrinkled. It was like, like I was, I was, I was, I was, I was like live pig on Charlie brown, who would just, you start clean, just start walking and you would, I would begin, begin wrinkling through the day. Um, but, but, but that kind of imperfection, um, it turns out is really inviting.

Barry Yeoman: And so, so people talk to me more. Um, I understood marginalization in a way that I might not have if I. If I didn't stutter. And so when I, um, I mean, I will never know what it means to be black or to be an immigrant or to be transgender or to use a wheelchair. Um, and, and, and I don't wanna inject any false equivalencies, but I know what it's like to have people underestimate you and to have something that puts you at a disadvantage.

Barry Yeoman: And so I tend to gravitate toward people like that rather than people in power. And I think that makes me a better journalist. So all this was a really slow recognition. But I got there and I mean, I still have, um, shaky moments. Um, but, um, but

Barry Yeoman: by and large, I can hold onto that, um, recognition that God, um, I, you know, these days I, every interview I do is recorded, um, at least audio and more and more video because of the pandemic and zoom, right. This. And so I watch those recordings. I, I I'm transcribing, or I'm looking for something and, and. I, I hear the stutter.

Barry Yeoman: I see the secondaries. Um, but what I don't see is me being a worst journalist for it.

Uri Schneider: When I, when I meet people that are going into career or, or wondering if they could be a good partner in a significant relationship. Uh, and there's this belief that, Hey, if I stutter, how could I possibly be a good husband? How could I possibly be a good father? How could I possibly be a good journalist lawyer, teacher, whatever.

Uri Schneider: Um, I, I borrow from my father, this idea, you ask them, well, certainly that's, that's a story and that's a belief that you've been living with, and you may have been messaged such a thing based on, you know, other people's measures and expectations. But I wonder if you go out there and you ask the person that you're looking to couple up with, Or someone like them or the interviewer at that grad school or at that job interview.

Uri Schneider: And you wonder, what are the top five qualities they're looking for? What are the top five qualities of a journalist? And you'd probably have a bunch you, you would know better than me. I'm not even gonna step there, but, but fluency probably isn't in the top five or top 10. Yeah. And, and as a person who stutters how important it is to figure those things out and realize you might be average or above average in many of those.

Uri Schneider: And if you go in just worrying about your stutter, managing your stutter, and even if you manage it quote successfully, and you don't stutter, you don't stutter as well as much. Uh, you might fail to show them what they're really looking for, which is not how well you manage fluency, but how well you can do the job.

Uri Schneider: Yeah.

Barry Yeoman: Yeah. Um, it turns out there are a lot of journalists who stutter. Um, I, I. No, because I hear from them. Um, and I don't wanna romanticize this. Um, I know that there are people who stutter, who get turned down for jobs because of the stutter, um, including jobs in journalism. I am one of them, you know, I, I, this was early in my career, but I had an editor, um, call me like ready to offer me a job even before interviewing me.

Barry Yeoman: And then he heard my stutter and then he called back two days later and said, we're, we're actually like reconfiguring our staff. So we're not gonna hire for that job. And I said, it's the stutter? And he said, yes, uh, this is a job. That's gonna be very visible in the community. We're hoping to break a lot of stories.

Barry Yeoman: And the, the, the, you know, the writer will probably be interviewed. On television. Uh, and, but if you're ever in town, let's have a cup of coffee. Um, no, thank you. Um, so, so there is, there is the external reality that some employers are not gonna hire people who have disabilities, uh, or people who, you know, who in any way defy their preconception of what a journalist is, but, and with, yeah.

Barry Yeoman: To, to, um, for you. Okay. Uh, but that, but, but, but that is different from how you perform as a journalist.

Uri Schneider: I, I wanted to just pull from you or challenge you to speak to those people, speak to those people who have those worries, who are anticipating that possibility or live with repeated experiences like that.

Uri Schneider: Being Barry, Yoman being someone who's lived through that, being someone who's aware of it. And at the same time, being a person who encourages people to pursue the path that is their path and be resilient and be who you are and be truthful to your calling. What wisdom, what, what encouragement, what message might you give to someone who feels they've been, um, precluded from access to a job or to a community or to a position based on their stutter?

Uri Schneider: What would be your, cause you said before also railing against them for discrimination in some cases might be important. Self-advocacy correct. Um, but it, at some times it might not be, could you share that on that?

Barry Yeoman: You probably didn't want that job anyway. Um, being precluded from a job is different from being precluded from a career.

Barry Yeoman: And you should not assume that one. Means the other, um, it will be harder because you stutter because there are, uh, ignorant and in some cases, malicious people in the world, um,

Barry Yeoman: but

Barry Yeoman: this country, this world is full of journalists who have, who stutter and the, the, the ingenuity that you bring to navigate past other people's discriminatory practices will in the long run strengthen you. It is hard to believe it in that moment, in that moment, it just hurts. And, um, I don't wanna downplay that.

Barry Yeoman: Uh, you might feel weak, you might feel like a failure and I don't wanna say buck up, you know, um, but eventually buck up and, um, like, like, like not immediately, not immediately, you know, feel the feelings, but then recognize my first editor. I will name him James Edmonds at the times of Katya in Lafayette, Louisiana.

Barry Yeoman: He hired me for a job straight out of college. Uh, he was technically not my first editor because I had part-time uh, sure, sure. Journalism jobs. But by my

Uri Schneider: first there there's a journalist making sure he's on record and being accurate. That was

Barry Yeoman: beautiful. Yeah. Footnote. Right. Um, but James called me and got me in a newsroom where I was basically freelancing in college and he had like gotten my application to fill this job.

Barry Yeoman: He didn't know anything about me other than three newspaper clips I had sent and a resume. And he calls me and I stuttered severely on that call. And he later told me that when he hung up at the phone, he thought to himself, that's the guy I wanna hire because the. He did the work that I just read with a stutter and that shows what kind of go-getter he is.

Barry Yeoman: And you only need one James, because once you get the first James, then the dominoes of resistance start to fall.

Uri Schneider: And what I, if there's one thing I could take from all these conversations, Barry, is that message. It seems that every person, and I think it extends also to people that don't stutter, but anyone that certainly has had any sort of adversity, someone opened a door and just opening that door one time, it opened a floodgate, you know, just crack the T wood says you open the door for me, just a crack.

Uri Schneider: I'll take it the rest of the way. We've all gotta put in the effort to swing the door open, but someone's gotta unlock it for us. And if we're in the position, what I wanna flip around, especially this time of year giving and, and paying forward, if we're in a position to open a door for somebody to recognize the power of that gift, and it could be nothing, it could be taking a phone call and giving someone our attention, our ear, our wisdom, our experience, it could be making a phone call or an introduction.

Uri Schneider: It could be looking at a resume and, and just offering some feedback from the perspective that we have. We don't know the significance of that act, but it can be life changing and many of us have benefited from it and we have to recognize we all have that chance to pay it

Barry Yeoman: forward. Thank you for that. I am bold over by feedback.

Barry Yeoman: I get about things that I don't even re remember that I did. I I'll run in to somebody who, you know, I taught seven years ago or who I. Had coffee with cuz they were thinking of a career in journalism or I, I wrote a letter of introduction and they'll say, um, you were the first person who ever told me I had talent.

Barry Yeoman: Um, you were the first person who ever introduced me to a future employer. Um, you know, you wrote me the letter that got me, my first job and look where I am now. And at the time it really did, it did seem in inconsequential to me, but it's not, it never is. Um, that's been, that's been such a, such a surprise.

Barry Yeoman: I remember the first time I put a hand on each shoulder of a student of mine and looked him in the eyes and said, do you know how proud I am of you? and that was scary for me because it was exercising my authority in a way that I hadn't done very often, but I saw, I saw a change in that moment

Uri Schneider: and we know in education, people will perform up to the standard that you hold them to. Vivian Siskin talked about it with Joseph sheen, and I see that in life and practice so much. We're gonna wrap in just a few moments. I wanna give Barry the final word and chance to share the nuggets. He has so much to pour forth.

Uri Schneider: I'm gonna share one quick story about resumes and jobs specifically, cause it's just perfect for this moment. And then give Barry a chance to take us home for this conversation. This round, um, a young man came to me. He was a young man. He finished college. He was a big athlete, big. Fine specimen of American athleticism and brains and an MBA student and a high level collegiate athlete.

Uri Schneider: And he was networking on LinkedIn and, uh, dealing with a lot of head hunters and things. And so we were talking about how to put his stuttering on the radar because picking up the phone or showing up for the interview, as Barry said, you know, it can look good on paper and then you get on the phone and you stutter.

Uri Schneider: And sometimes people don't know what to do with that. And sometimes the consequences are the difference between getting the job or not. And I'm a big believer. It's part of this transcending stuttering academy that we're working through. Self-advocacy how do we tell the story? And as Barry said, in a way that's not militant or adversarial, but is informative and creates bridges and creates confidence that people have in your ability and your integrity and your perseverance and that you're not intimidating.

Uri Schneider: Uh, so I, I came up with an idea that this guy should put on his resume in his volunteerism. That he volunteers as a mentor for other kids who stutter. And in that way, he's putting the stuttering on the table before he even gets on the phone or has the call with the head hunter, but it's totally non apologetic.

Uri Schneider: It's totally non anything. It's turning it around into an asset. If I've lived through an experience of having a stutter. And these are my accomplishments on the top section. And in my free time, I offer mentorship. That was a year ago, Barry. I met a young teenager who also plays lacrosse, same sport. He's a junior high kid on the east coast and I'm working with him and he's got all kinds of worries about stuttering.

Uri Schneider: And I tell him, you know, I think I have a mentor for you. I just, haven't been in touch with him in about a year. The next day I get an email from Gary, the guy that I had met the year before, and I said, Hey, and he tells me an update. And I said, how would you like to be a mentor? He says, I would love it. I would love it.

Uri Schneider: So I told him at the time you could only put it on your resume if you truly. Whether it's through one of these organizations and he has joined NSA programs and friends has UN wonderful programs say has wonderful programs, but the idea of giving back, you don't just give you also get, so just wanna encourage all of us in whatever way we can, whether it's monetarily foundations and organizations need help, whether it's, you know, giving the time and attention or, or a message to young.

Uri Schneider: Person's so, so important, especially now. So, Barry, this has been amazing. People are drinking it up, take the time to just share whatever you'd like to just pack in here before we say good day.

Barry Yeoman: I think I do have just one more thing to say, which is so earlier, early you were talking about, um, some of the giants in the stuttering world, you know, the Michael Sugarman's.

Barry Yeoman: Um, and so many of those folks, um, gave to me. um, at that very first self-help meeting with national stuttering project, you know, John Uck, um, who is executive director at NSP changed my life. Um, but I wanna add that, that the tr the, I thought the generational transfer runs in both directions. Um, I took a break from American stuttering self-help for a decade, um, from, from 2004, the year that I asked Joe Biden, that question until 2014, when I realized I missed my friends and I needed to come back.

Barry Yeoman: And I, and I had been to a couple of international conferences and, um, in that period, but I had not been, I took to an American one and when I came back, there was a new generation of thinkers. Um, uh, I think about people like Chris Constantino. Um, I think about all the folks in the leadership of the New York city chapters of NSA, uh, and, um, NYC stutters, um,

Uri Schneider: next week.

Uri Schneider: Yeah. Next week, Matthew Beka actually is joining me next Thursday. He co-leads the Brooklyn chapter wonderful guy. Yeah. As well as all the

Barry Yeoman: rest. Yeah. Yeah. Um, and, and in those first years I came back, I met, you know, Rosh and sta and Emma and, and HYA and mark and mark, um, mark and mark, mark and mark. Yeah.

Barry Yeoman: Um, and they were untainted by some of the. Tensions that had gone on, you know, in schools of thought about, about how, um, how proactive people who start should be politically, how much we should involve, uh, SLPs in shaping our mission. Um, like all the stuff that, uh, was a robust and sometimes tense conversation in the stuttering world that was before them.

Barry Yeoman: And so they came in fresh and clean and we, we had a set of ideas that, um, that I was so ready to hear. And those really were the leap from it's okay. To stutter, to it's kind of great to stutter. And so when someone like. Like Chris Constantino talks about how stuttering makes us more vulnerable. And that allows for more intimacy in our conversations, um, which is real, which is palpable when, um, when somebody like Josh St.

Barry Yeoman: PIRE, um, air, um, historian in Canada, a co-founder of did I stutter talks about how, um, Stu how stuttering, um, moves us away from the measurable efficiency of modern life. You know, the, the industrial production standards of, of 21st century America, and brings us back to more natural ways of measuring time.

Barry Yeoman: Be it, uh, agricultural cycles or lunar cycles or menstrual cycles. Um, When Emma Alburn writes about how stuttering can be exciting, um, and like a type of dance where, you know, Fred ISTE trips, but then he doesn't fall. Yeah. All those ideas and more, um,

Barry Yeoman: we're so instrumental in helping me make the leap to this last phase, this most recent phase of my contemplation of stuttering. Um, that is wisdom. I got not from the last generation, but from the one after me. And so, um, so I just wanna, uh, thank those who came before me and those who have come after me because we all fuel each other.

Barry Yeoman: In surprising and growthful ways.

Uri Schneider: Wow. So just to riff off that, I want to thank you. It's those that come before those that come after and those of us that have the fortune to meet in the middle, um, we, we gain from both sides and, uh, I think the message I'm taking, if I can just, uh, say it in a, the way it comes through me, what you just shared, each of us individually are on a journey and growing.

Uri Schneider: Um, we have to look back at those that set the groundwork for us, and they have a lot that they've put in place that wouldn't be here. We wouldn't be benefiting from if not for their efforts and initiatives. And, and it doesn't go one way, right? It's a reverb kind of goes both ways. And, uh, that people like you tipping a hat to those who are now in positions of raising their voices and contributing to the community.

Uri Schneider: So each of us is evolving. The community is evolving and the world's evolving and the best way forward is when we recognize the contributions, both of those before us, those that stand with us and those that are maybe younger than us, but offer a fresh eyes and offer fresh new addition. There's nothing it's not complete.

Uri Schneider: There's there's room to add your, your piece and your voice. And we all have a piece to add. So that's stunning.

Barry Yeoman: Uh, um, amen.

Uri Schneider: So thank you everybody. I'll end it here. If you wanna check out, I'll just make the plug the next step of 2021. If you go to Schneider speech.com/. T S a as in transcending stuttering academy opportunities for speech therapists and for people who stutter to take it forward from these conversations.

Uri Schneider: But thank you, Barry. I wish everyone stay healthy, stay strong, share the conversation, comments likes, and I'm sure Barry and I will make our efforts to respond to the comments that we can, but we appreciate all of you. And thank you for sharing the time with us.